A few days ago, I was reorganising my GitHub account, a weak attempt to revive it from inactivity, and I stumbled on a project I had done during my MSc, which involved network analysis for the TV show Game of Thrones. A Network analysis looks at how things are connected and helps identify who’s most central in the web of relationships. It is one of my favourite projects from school and also one of the courses I enjoyed the most, a big shout to Professor Jaromir Kovarik.

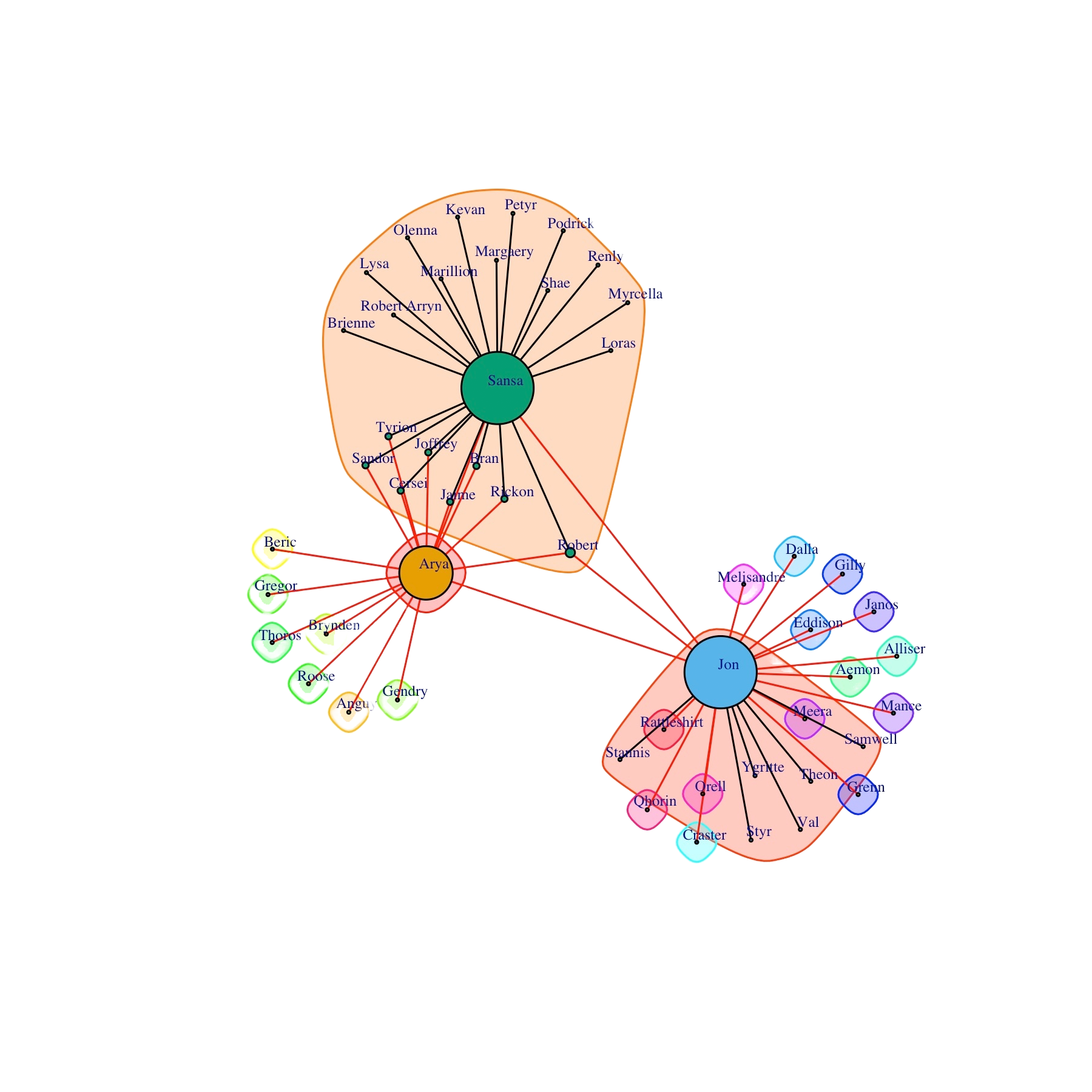

My analysis focused on House Stark, and through it, I discovered how characters like Sansa, Arya, and Jon each anchored their distinct clusters. Sansa, in particular, stood out not just because of her screen time, but because of how many relevant figures were connected to her. You can see the analysis on my github.

In network analysis, certain metrics help quantify how important a node is. One common measure is degree centrality, which simply counts how many direct connections a node has. Others go deeper, like betweenness centrality, which captures how often a node acts as a bridge between two others. And concepts like hub and authority scores reflect: the difference between knowing important people and being known by them. After that project, it made sense to me why it was a great writing decision for Sansa to be made Queen in the North. Because influence isn’t just about how loud a character is, but about how well-positioned they are in the network, and for House Stark, Sansa occupied an extended depth and breadth of their network.

That exercise reminded me of something I’ve thought about every now and then: networks and how our world depends on them. Networks are the hidden backbone of almost everything that matters. In how machines learn to mimic us, in how our relationships amplify both connection and isolation, in how nature organizes intelligence and even how cities pulse and adapt like living things. More interestingly is that they do not have one way of showing themselves; they manifest differently depending on which system the interactions are happening.

Think of artificial neural networks, for instance, it’s just a mathematical function that attempts to mimic how the human brain processes information through interconnected neurons, and is now largely being applied in AI. If you deep dive a little into ANNs, you will see that they are themsematicalelves a combination of two or more artificial neurons. Because a single neuron has no usefulness in helping solve real-life problems. What gives a neural network its power isn’t any single node, but the pattern of connections between them. Their intelligence emerges from the architecture of their network.

Human networks are harder to measure but very real. We form them through families, friendships, organisations or even shared interests and ideology. Sometimes, deliberately and other times without much planning. And, just like in neural networks, there is a consistent feedback loop, attention breeds attention, and silence breeds invisibility. Online spaces have made these networks more visible, but more complicated, as there can be an illusion of closeness that is not entirely true. This is because in human networks, power doesn’t lie in being the loudest, but in being the most connected. In a few cases, however, being loud enough can also signal to members who become part of your network.

But before we learned to form these connections or even name them, nature had been working with networks. The forest is linked underground by fungal networks that let trees share nutrients, warn each other of danger, and regulate the growth of new life. These biological networks show us that networks arise from relationships, rhythm, and responsiveness. One of the early concepts I learned in high school biology was about the codependence of species on one another to survive. This is where the concept of symbiosis lives, and symbiotic relationships can be beneficial or deadly. There are four main categories: mutualism, commensalism, parasitism and competition. Once you start edging towards parasitism, there is danger. You can see this reflected even in human relations. It’s why people who appear to always want to benefit from a network are often referred to as leeches. Most leeches are ectoparasites, parasites that live outside the host and feed off of it.

I have heard a lot of times that if bees go extinct, so will the human race. I used to find this outrageous till I learned more about pollination. Bees (especially honeybees and wild pollinators) are crucial to pollination, which is the process that allows many plants to reproduce. I mean, we may not technically go extinct immediately but there will be a lot of problems.

Just like humans, I consider cities to be living, breathing things, because they contain a vast thread of systems – roads, subways, power lines, water pipes – that make our daily lives possible. In fact, one of the worst things that could happen in our modern civilization is a mass prolonged power outage, because of how so many of our modern structures depend on electricity and how other things depend on them. We had a tiny glimpse of the possibility for disaster, recently in some parts of Europe where people were stuck in trains for hours, some were stuck in elevators, others lost access to the internet after a power outage.

Everything is a network, or at least, everything behaves like one. Once you see through this lens, you begin to challenge the idea of control, you will see that no one fully owns or leads a complex network because influence spreads through connection, not command.

Outside of connection, feedback and adaptation also strengthens networks and their individual members. I will recall the Hebbian theory, neurons that fire together, wire together. If two nodes, whether it is people, ideas or institutions frequently co-occur or co-influence, the connection between them is strengthened.

Some materials that helped with this article:

Kenji Suzuki’s Expansive research on ANNs.

Mitchell Melanie’s Book on AI.

This article on Symbiosis by National Geographic.

My random thoughts and recall.